Since premiering on Netflix four years ago, Love Is Blind has produced eight marriages, two soon-to-be babies, a couple of divorces, too many messy breakups to tally, and dozens of hours of entertaining—occasionally appalling—reality television.

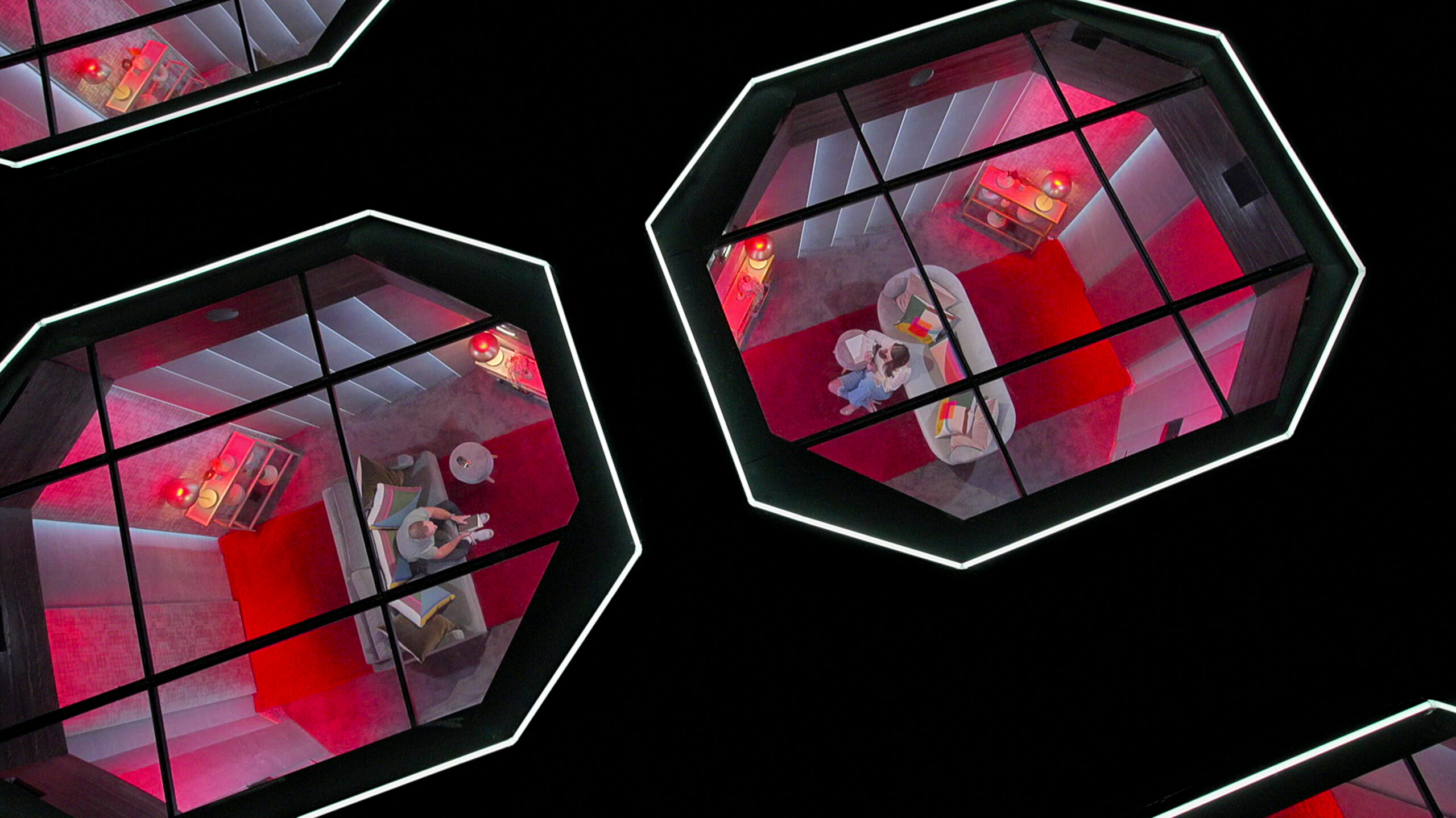

On Feb. 14, the show’s sixth season starts streaming, this time set in Charlotte, N.C. Hosts Nick and Vanessa Lachey will once again guide a group of people eager to find love—and/or social-media followers—through a dating scenario designed to determine if love really is blind. After getting to know each other through a wall in small isolation rooms called pods for about 10 days, participants get engaged without ever having seen each other, and then spend a month living together before meeting at the altar to commit or break it off.

If you already know all this because you can’t look away, you’re in good company: Relationship therapists also love Love Is Blind, and not because they’re scouting for future clients. “It’s just fascinating to see how people connect and relate when they don’t know the external context around financial status and looks and all the things that factor into how you judge a person,” says Julia Baum, a therapist based in New York who’s watched every episode. “It’s really neat, especially when you see people who you wouldn’t expect to connect in the pods.”

That said, there are plenty of ways the show could improve. We asked therapists what they would change about Love Is Blind if they were showrunners for a day.

The casting should branch out

Contestants on Love Is Blind don’t know what the people they’re dating look like—but they can reasonably guess that they’ll like what they see. The show has notoriously cast conventionally attractive people with little body diversity.

Ideally, casting would diversify in numerous ways, says Nicole Hind, a couples therapist based in Australia. For one thing, age: Many people on the show are in their 20s or early 30s. What about a season featuring singles 40 and older?

She also urges producers to bring on contestants who don’t fit into a certain appearance mold, including those who have a disability or a heavier body weight. And it would make things more interesting if various sexualities were featured. What if Love Is Blind featured openly bisexual, asexual, or pansexual people? Hind suspects it would be a hit: “This is one of the reasons people watch reality TV,” she says. “To see a window into others”—or to have their own identities reflected back at them in some way.

Let the contestants touch each other

Love might be blind—but sight is only one of five senses. To spice things up, Michelle Herzog, a relationship therapist in Chicago, suggests tapping into a few of the others. Imagine if blindfolded contestants could hold hands with or otherwise touch the person they were considering marrying. “I think it would be really impactful in helping people decide between two people,” she says. “Physical touch releases a hormone called oxytocin, which is nicknamed the bonding hormone. It promotes closeness, connection, and intimacy, and can fuel feelings of attachment.”

And let’s not overlook smell: A freshly worn T-shirt could be waiting in the pods for someone’s potential match—providing a sense of their cologne or perfume, for example. Catching a whiff could help participants “learn more about this person, outside of words,” Herzog says.

Warn contestants of red flags

Johana Jimenez, a therapist based in Addison, Texas, wants contestants to know important details about who they’re dating through the wall. During the first three dates, each person should enter the pods to find a letter that reveals one green flag, or positive attribute, about the contestant they’re getting to know. “It could be education or income or an entrepreneurial spirit or that they love to sing”—some other tidbit that producers suspect the person’s potential fiancé would appreciate, she says.

After three dates, as the relationship became more serious, producers would start delivering red flags to the pods, but this time, the envelopes would disclose deal-breakers that the producers had discovered during the casting process. In season five, for example, Stacy Snyder might have been informed of Izzy Zapata’s bad credit score, which she was frustrated to learn about weeks after leaving the pods and ultimately contributed to their breakup. “Sometimes contestants don’t bring up things that are crucial for the other person to know,” Jimenez says. “And I know it makes for good drama, but people are getting their hearts broken.”

Let the games begin

Love Is Blind tends to skip the games and challenges that are core to other reality shows. But that’s a missed opportunity, says Amy Morin, a psychotherapist based in Marathon, Fla. Solving problems or tasks together, or competing against each other—like Love Island contestants do—could be insightful. “You would get to see somebody’s true character. Are they trying to cheat to get ahead? Are they super competitive? Do they not really care? It’s not just about what they say, but about what they do, and how they do it.”

Give them therapy (and let us watch)

Aside from the show’s celebrity hosts, contestants are essentially left to their own devices to figure out who to get engaged to, how to navigate the inevitable conflict that arises, and whether they should get married. Maybe she’s biased, but that sort of stress calls for an on-screen therapist, says Stephanie Yates-Anyabwile, a marriage and family therapist based in Decatur, Ga., who posts Love Is Blind reaction videos on YouTube.

Ideally, a therapist would hang out in the lounges where contestants gather with other participants of the same sex when they’re not on pod dates, helping them work through their emotions from the day. A cast member could say, “‘Hey, I’m having a hard time choosing between two people,’” Yates-Anyabwile notes.

Therapists could also supply contestants with a list of questions to ask their potential spouse, says Luree Benjamin, a marriage and family therapist in Henderson, N.C. For example: What are their do’s and don’ts when it comes to anger? “Is shouting and slamming doors allowed? Is walking out?” she asks. “How long do you stay disconnected from one another?” It would also be smart to explore how the other person feels about social media—and the extent to which their post-show lives would be broadcast to new followers.

Let them phone home

The pod environment is “very much like a pressure cooker,” says Mickey Atkins, a therapist based in Tucson, Ariz., who posts YouTube videos about the show. “From a mental-health perspective, it’s disappointing to see people be isolated from their family and friends and normal support system,” she adds. Not being able to process their decision verbally with someone they trust, she believes, is one of the reasons many couples don’t last. To address that, the show could implement a phone booth in which contestants could call home. That way, instead of feeling cut off from comfort and familiarity, they could ground themselves by checking in with a loved one.

More women should propose

Women rarely propose on Love Is Blind, though the show’s creator has said in the past that it’s allowed. In an ideal world, women would account for at least half the proposals, says Baum, the New York therapist. “The assumption that women on the show are ‘ladies in waiting’ is toxic,” she says. “I think it would be better for viewers to have that normalized: a woman can take that initiative.” In addition to helping shatter archaic norms, Baum points out, imagine the insights that could be gleaned about a future partner. If a man is offended that his grand moment was stolen, maybe he’s not such a catch.

Bring a third-party advocate on set

Past Love Is Blind contestants have spoken out about the way cast members are treated during filming, and at least three have filed lawsuits for reasons including sexual harassment and even false imprisonment. To ensure future contestants aren’t exploited or harmed, psychotherapist Kirk Honda envisions a third-party advocate who’s always on set. This person, he says, would operate similar to the intimacy coordinators who have become standard in Hollywood. “These are hired individuals who have power and can step in and say no,” says Honda, who hosts the Psychology In Seattle podcast and YouTube channel, and often posts Love Is Blind reaction videos. “Or they’ll pull aside cast and say, ‘How are you? Does this feel OK?’” Such a change would also help viewers feel better about tuning into sometimes-unethical reality TV.

Limit the alcohol

The golden goblets featured on Love Is Blind get more screen time than some of the contestants. Alcohol appears to flow heavily—and past participants have alleged they were encouraged to drink. Atkins has an idea: moderation. Cast members could be limited to a certain number of drinks each day, or urged to abstain. “Sober people make better decisions about their lifelong legal and financial entanglements,” she says. With marriage on the line, in a highly unconventional situation, contestants would do well to be as clear-minded as possible.

Focus more on the love story

Reality TV doesn’t always reflect reality. If Honda were in charge of Love Is Blind, he’d be more truthful in the edit. In season four, for example, Jackie Bonds was portrayed as rekindling with former suitor Josh Demas before breaking things off with fiancé Marshall Glaze. The alleged infidelity prompted outrage among fans—but as the stars later confirmed, events were shown out of order. The two had already split. “When we learn that lies are occurring, it loses all of its power and appeal as a ‘reality’ TV show,” Honda says.

Yates-Anyabwile seconds that notion: She would rework the show by focusing more on the love stories, and less on manufactured drama. “I think we’ve come to believe that drama brings in numbers,” she says. “But it’s becoming too much—you start losing interest and engagement after a certain point.”