As we head into winter, health experts expect that cases of flu and COVID-19 will start to creep up. One piece of good news: if you do get sick, there’s a way to get tests and treatments for both—without paying a cent.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have teamed up with digital health company eMed to create an at-home test-to-treat program that offers free tests for both flu and COVID-19, and, if you are positive, free telehealth visits and antiviral treatments that are sent to your home.

For now, there are some restrictions about who can enroll and receive the free tests. After the program officially launched last month, following a flood of requests from people eager to stock up on the tests, NIH and eMed decided to prioritize people who could not afford them, including those without health insurance and those on government plans such as Medicare, Medicaid, and Veterans Affairs coverage.

But the treatment part of the program is open to anyone over 18 who tests positive for flu or COVID-19, regardless of whether they used one of the free tests from the program. People who enroll will be connected to a telemedicine provider via eMed, to discuss whether they could benefit from an antiviral treatment. For the flu, that includes four approved drugs:

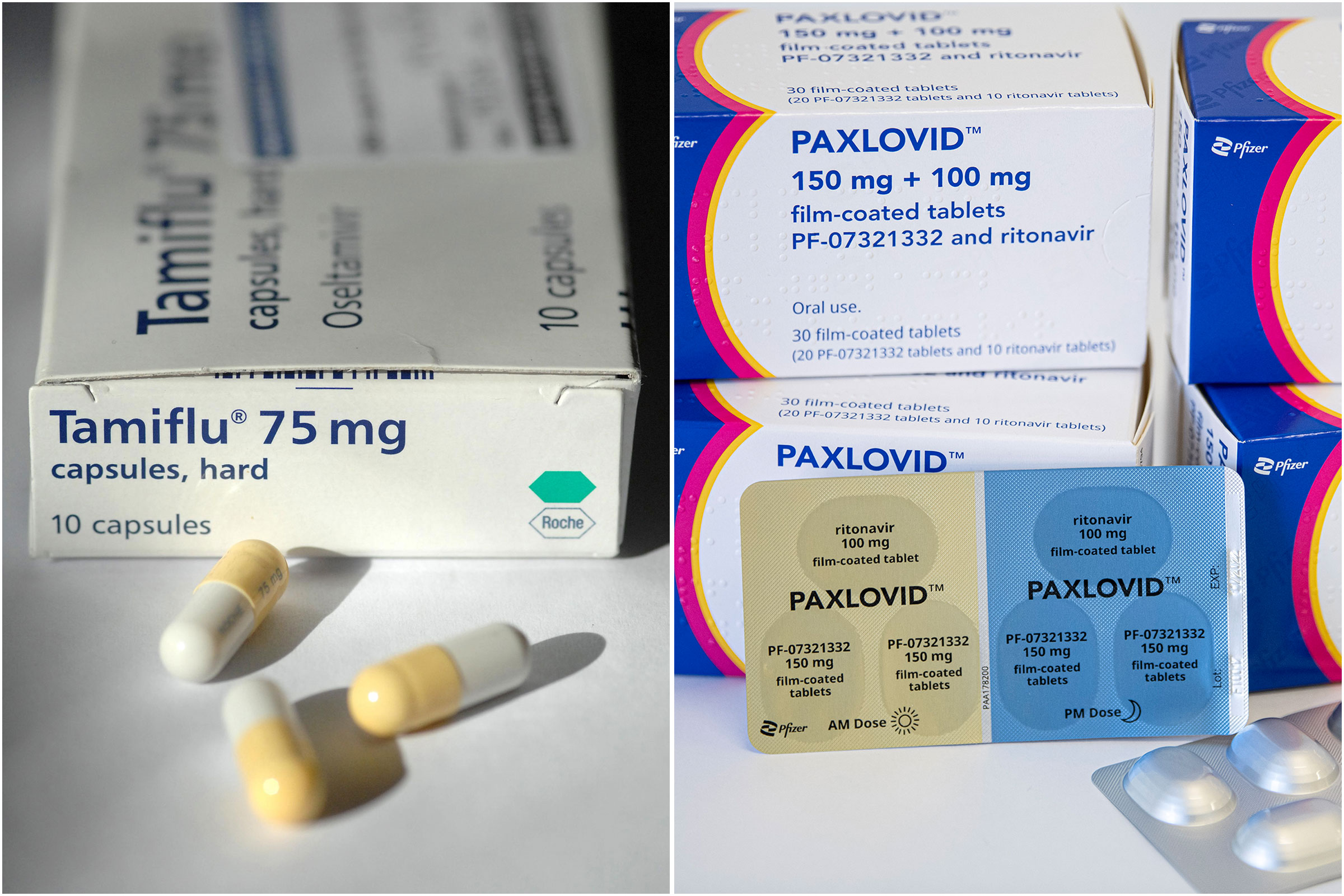

- Oseltamivir (Tamiflu)

- Zanamivir (Relenza)

- Peramivir (Rapivab)

- Baloxavir marboxil (Xofluza)

For COVID-19, there are two approved oral medications to choose from:

- Nirmatrelvir-ritonavir (Paxlovid)

- Molnupiravir (Lagevrio)

While there is one other approved COVID-19 treatment, remdesivir (Veklury), it’s an intravenous infusion that requires medical professionals so likely won’t be widely prescribed through this program. Dr. Michael Mina, chief science officer at eMed, expects that doctors will most likely rely on Tamiflu or Xofluza for flu, and Paxlovid for COVID-19.

The idea behind the program is to see if moving testing and treatment out of the hands of doctors and into those of patients will increase and speed up access, ideally reducing spread of flu and COVID-19. “We imagine it will benefit people who live in rural areas who can’t easily travel to health care facilities,” says Andrew Weitz, the NIH lead for the Home Test-to-Treat program, “or people who get sick over the weekend and aren’t able to immediately see their primary care doctors.” The antiviral drugs for both influenza and COVID-19 are most effective when people use them within days after symptoms start—one or two days in the case of flu, and five for COVID-19. So shortening the window between when people notice their first symptoms and when they take their first antiviral pill could substantially reduce the time they are sick. And having a supply of tests on hand could be a way to move people from symptoms to treatments even sooner.

If you qualify, the test you receive in the mail is a single kit that combines COVID-19 and flu, and it’s more sophisticated than the rapid-antigen COVID-19 tests. It’s a version of the gold-standard molecular, or PCR, test that labs use and looks for influenza and SARS-CoV-2 genes. “It’s actually an amazing deal for [those who qualify] to get two free molecular tests,” says Mina, since purchasing them would cost about $140. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration is expected to authorize a cheaper rapid-antigen test that detects both flu and COVID-19 in December; if that does happen, the test-to-treat program will offer those as well.

It’s all about moving the process for testing and treating the most common respiratory diseases out of the cumbersome health care system and into people’s homes. COVID-19 taught doctors—and patients—that almost anyone can reliably test themselves with a relatively easy-to-use kit. Couple that with a telehealth option for people who test positive, and more sick patients could get prescriptions for antiviral treatments that can not only help them feel better but potentially reduce their risk of passing on their infection to others.

As part of the program, the NIH will also collect data to try to answer some important questions about the role of self-testing and test-to-treat programs in U.S. health care. For example, researchers will investigate whether such programs increase access to antiviral treatments, and if they raise the proportion of people treated in the time frame when the drugs are most effective. “One of our primary goals is to understand how quickly people go from feeling sick to the time they have treatments in their hands, and if this program can do that faster than someone who waits for an appointment with their doctor or at an urgent care, then has to go to the pharmacy for their medication,” says Weitz.

Researchers will send program participants who receive telemedicine visits and a drug prescription a survey 10 days following their visit, and again six weeks afterward, to get a sense for how many actually received and took the antiviral medications, as well as to ask broader questions about the rates of Long COVID among participants and how many experience Paxlovid rebound, in which infections return after people test negative following a course of the drug.

There will be a separate, more rigorous research part of the program in which many people who enroll will be invited to participate in a study, conducted in collaboration with the University of Massachusetts, that will help scientists better understand whether treating people early can reduce the spread of influenza and COVID-19, by asking whether other people in the infected person’s household got infected. That could enrich doctors’ understanding of how contagious COVID-19 is, how long people are infectious, and how effective the treatments are in reducing infectiousness. That in turn could help to refine current recommendations for how long people should isolate.

The program is an effort to “leverage the latest technology to meet people where they are, and hopefully have them avoid going to a health care facility and potentially infecting others,” says Weitz. “We are interested in understanding how to push the limits to provide alternative opportunities in delivering health care.”